The nature of transition

Foundational and whole-system changes will be needed to address the numerous interrelated problems within our food systems. We must act now with urgency because for decades we have ignored and denied these problems, and postponed meaningful action (cf. Bendell, 2018 on the climate emergency). Some decision makers acknowledged these problems, but excused them, or only proposed solutions that tinkered with the status quo (for thoughts on our collective inability to act, see Goal 3, Integrating food into educational processes, Redesign). Many have assumed that market signals and supports for technology innovation to stimulate market activity would shift business and consumer behaviour, but because of widespread market failure in the food system (see Get Started, Problems), this is not happening quickly. Such myopia now leaves us in a position where foundational ‘whole-system-redesign’ changes will be needed to avoid ‘collapse’ at every level within our food systems, from soils to our abilities to provide the nourishment to enable health and wellbeing. Popular and community interventions to shift culture and markets, although complementary, will not be sufficient on their own, given the depth of our challenges. Rapid system change requires significant government intervention using multiple instruments and business and personal transformation to push and pull behavioural, cultural, economic and technological change (cf. Johnstone and Newell, 2018). And governments will have to be pushed by well organized advocates to help this happen.

There is a growing new literature on transition, although some of it is conflated with innovation (El Bilali, 2019), in my view related but not the same thing. It is different from important transition/transformation theory that has explained earlier periods of socio-economic, science/technology and cultural change (cf. Polanyi, 1944; Kuhn, 1970; Schot and Kanger, 2018) because it focuses on driving change forward rather than focusing primarily on past phenomena. Some of the emerging literature refers to this change process as "pathways" (for an analysis of how this term is used, see Rosenblum, 2017).

El Bilali (2019) cites Loorbach and Rotmans (2010a) who define transition as “a fundamental change in structure (e.g. organizations, institutions), culture (e.g. norms, behavior) and practices (e.g. routines, skills)”. Several other authors have embraced the term ‘sustainability transition’ (Anderson et al., 2019; Falcone 2014; Geels 2011; Grin et al., 2010; Hinrichs, 2014; Kemp and van Lente 2011; Kemp et al., 2007; Lachman 2013; 2020; Loorbach, 2007, 2010; Loorbach and Rotmans 2010b; Markard et al. 2012; Padel et al., 2020; Sustainability Transitions Research Network 2010; Vinnari and Vinnari, 2014). Additional transition frameworks applied to the food system are reviewed by El Bilali (2020), with a summary here. Given the range of transition frameworks in use, there have been some attempts to create an integrated version (cf. Duru et al., 2014; El Bilali, 2020), but these are not in wide use.

Some transitions can only be described as unjust and unsustainable (false) transition. One example is what Swilling and Annecke (2012:181) define as “ecological modernization . . . via large-scale, top-down technofixes, co-managed by powerful corporate elites with access to new global funding mechanisms”. Sumner et al. (2019) name as an example the Nutrition Transition underway in many cultures (including indigenous ones) as a result of the (corporately and industrial state driven) adoption of the Western Diet and associated increases in Western diseases. Another is the deceptively simple solution, commonly presented by authoritarian leaders. The deceptively simple solution looks appealing but fails to address the root causes of the problem, and fails to advance positive change. Real change, however, often involves the profoundly simple solution, one that addresses multiple problems at the same time using elegantly designed strategies (see Stuart B. Hill). Just transition "emphasizes the key principles of respect and dignity for vulnerable groups, the creation of decent jobs, social protection, employment rights, fairness in ... access and use, and social dialogue and democratic consultation with relevant stakeholders ..." (IPCC, 2022; Chapter 17:30). Equally important is attending fairly to what gets left behind, what has to be downsized during transition.

The transition to sustainability is also about changing our inner world, our values, beliefs and motivations for action or inaction, sometimes referred to as the inner transition to sustainability (see also Get Started, Advocates for Change, Inner Transition). As part of this, numerous psychological theories of behaviour and behaviour change have emerged (cf. Ives et al., 2020; also Contributors, Stuart B. Hill). “[W]e need fundamental shifts in values that ensure transition from a growth-centered society to one acknowledging biophysical limits and centered on human well-being and biodiversity conservation”. (Martin et al., 2016:6105). A number of studies highlight that elites "are hard-wired to ignore environmental risks that could question their individualistic and meritocratic worldview" (De Schutter et al., 2019:379). Without changing their psychological reality, information alone will not cause behavioural change. Art, in its many forms, and artists can also be important parts of shifting individual and societal consciousness for social transformation (Waddock, 2021). Habermas (1979) articulated how cultural value shifts can echo the maturation process of individuals, as certain ways of thinking become acceptable and are deemed reasonable. Presumably this applies to the cultural transformations to a just, health promoting and sustainable world.

What does transition need? A vision of the future is required, with conceptual frameworks (see Frameworks) and sometimes modelling tools that inform that vision. Methods and instruments to implement the vision are also essential (see Instruments). Those implementing change must be willing to following different processes and use different structures and organizational forms to achieve the vision. The attitudes, beliefs and realities of actors involved in change are important to understand, as are the development of skills and capacities, which must usually be refined as a transition progresses. For that refinement to happen, there must be systems of monitoring and evaluation as different elements of the transition are implemented (adapted from Senge et al., 1994; Beers et al., 2014).

A critical feature of transition is improving our collective ability to manage and implement in complex environments. Canada is quite weak in this regard which is another reason why evolutionary transition is important: it will take us time to "up our game". Although some are naturally adept at it, in general, training in complexity management is poor at all levels and many of our current challenges flow from poor complexity management skills. Improving the ability of decision makers to manage in complex environments is foundational for successful implementation of the proposals outlined on this site.

Different frameworks have merit for different kinds of investigations and purposes, with different kinds of agents. There are debates in the literature about who agents are, and what power they have, compared to systems and structural changes, to influence change (cf. Fischer and Newig, 2016; Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016; Kohler et al., 2019; Koistinen and Teerikangas, 2021). Most of the transition literature fails to incorporate a critique of capitalism and it's role in impeding transitions to sustainability (Feola, 2019). Many frameworks are passive, attempting first to categorize past and current events that are not necessarily actively driven by change agents toward a different future. Other frameworks are more actively directive or normative (see Home Page). I find the Hill and MacRae (1995) Efficiency – Substitution – Redesign[1] framework the most helpful for taking an active and normative approach, and identifying a wide range of solutions to the wicked and messy problems of the food system. Although there is some debate in the literature, food policy and food system problems are often named as wicked (cf. Peters and Pierre, 2014). Their "wickedness" means they are difficult to implement, in part because resolution touches on many other issues at different scales (Chalifour and McLeod-Kilmurray, 2016). Similarly, messy policy problems need solutions that “... foster integrative actions across elements of multiple sub-systems” (Jochim and May, 2010:304), and require collaborative interventions from a range of actors (Head and Alford, 2015).

This ESR framework helps to make sense of changes, and serves as both a guide to action, and an indicator of progress. For any particular change area, it helps to bring together a sense of immediacy and practicality (the Efficiency stage) with a vision of the future (Redesign). In this framework, Stage 1 strategies involve making minor changes to existing practices to help create an environment somewhat more conducive to the desired change. The changes would generally fit within current policy making activities, be familiar to food system actors and eaters, and would be the fastest to implement. However, change strategists must be careful not to choose strategies at this stage that reinforce existing problems. In other words the design of actions and instruments is critical (see Instruments).

Second stage strategies focus on the replacement of one practice, characteristic or process by another, or the development of a parallel practice or process in opposition to one identified as inadequate. At the substitution phase are new organizational arrangements, the substitution of processes and practices, and consistent with Geels (2011), alternative / niche activity introduced into the dominant flow of change. There is typically more resistance to these changes, both within implementing organizations, and among those affected by the change. Issues of power and how it is exerted become particularly important at this stage. Navigating these tensions with different frameworks and processes is critical (cf. Kelleher, 2023). What instruments might move firms from efficiency measures to this stage? At this stage, advocates must be careful not to install infrastructure that will not be used at the redesign stage.

Finally, third stage strategies are based fully on the principles of the ecologies, particularly agroecology, organizational ecology, political ecology and social ecology, and are fully elaborated to address complexity (the earlier stages benefit from an understanding of complexity, but are not in themselves necessarily complex to execute). They take longer to implement and demand fundamental changes in the use of human and physical resources. Although "leapfrogging" is possible (cf. Perkins, 2003) and actors working independently without significant directed support may mix elements from all three stages at the same time (cf. Padel et al., 2020 on the transition to organic farming in the UK), this final, or redesign stage, is unlikely to be broadly achieved in Canada until the first two stages have been attempted. Ideally, strategies should be selected from the first two stages for their ability to inform analysts about redesign (the most underdeveloped stage at this point) and to contribute toward a smooth evolution to the redesign stage. This process is sometimes referred to as "radical change in incremental steps” (Fischer-Kowalski and Rotmans, 2009). There is usually substantial scaling up and out from the Substitution stage, and this scaling up and out can be vertical, horizontal, or emergent (with both active and passive elements). Moore et al. (2015) talk about scaling up, scaling out and scaling deep and my interpretation is that the shift from Substitution to Redesign strategies captures the "deep". This scaling must always be mindful of how place, practice, power relationships and culture impact what works. In other words this is not a scaling to generate the homogeneity that characterizes the dominant system, but rather scaling that reinforces diversity, consistent with ecological approaches (see Ferguson et al., 2019).

Since in complex systems and changes there are intersections between scale (Gunderson and Holling, 2002) and also across systems (Homer-Dixon et al., 2015), there is also a dynamic interplay between the stages and the issues being addressed. Some issues have received considerable attention and therefore efficiency and substitution stages are more advanced than an issue that has received little attention.

Unlike strictly academic work, I do not provide all the evidence to support in which stage of transition I place solutions. In general, my decisions are based on my experiences with decision makers as an advocate, on my work with many roundtables of food system actors, and on the literature that describes the public's perceptions of current realities and possible solutions to pressing problems.

A presumption of this framework, then, is that policy change in the Canadian food system is largely evolutionary. Change does not necessarily happen in an orderly, even and rational way, but a staged reformist approach allows the dominant structures to adapt progressively to policy pressures. But given existing pressures, the transition must be accelerated. The joined up food policy frame does not need to have deep resonance with policy makers and the public in the early stages of transition, but can build over time, a key consideration given the challenges of food system change. It is more at the substitution stage where such resonance must be significant to mobilize resources. The redesign stage is visionary but presumes progressive layers of transition leading to its realization. It is the most difficult stage to write about in detail because very limited modelling using redesign concepts has been undertaken, and the detailed plans may not become clearer until the Substitution stage has been achieved. We assume that there are no changes to the Canadian constitution and this limits what and how redesign efforts can be brought to bear[2]. As highlighted in MacRae and Winfield (2016) and further elaborated under Constitutional Provisions, the Canadian constitution is a significant brake on food system innovation and we account for that in these proposals.

Embedded in this framework is the notion of policy success, that interventions can actually achieve what they set out to do. The policy evaluation literature is itself contested, and the track record of many policy interventions is poor, but the ESR framework also integrates contestation as a reality of the change process. In other words, policy success can not simply be assessed based on whether everyone agrees with the changes since achieving sustainability, health and equity will always be contested by those who defend the dominant system (see Frameworks, Indicators, Monitoring and Evaluation for more). The best that can likely be achieved at each stage of transition is a "resilient success" (McConnell, 2010), whereby the changes are preserved, albeit with regular adjustments and shifts as the transition unfolds, there is generally broad legitimacy and relatively minor contestation of the changes, the participants in the changes largely agree with some disagreements but not sufficiently so to destabilize a coalition acting for change, and the changes are largely supported by the population. In this scenario the outcomes are largely, but not completely, achieved and the benefits distributed as intended, albeit with adjustments required of those most able to adapt to the new realities (typically the more economically powerful).

It is also clear that major policy mixes will be required to generate success (see Instruments). "[A] policy mix encompasses more than just a combination of policy instruments; it also includes the processes by which such instruments emerge and interact." (Rogge and Reichardt, 2016). But, unfortunately, there remains much debate in the literature regarding the characterization, implementation, interactions and effectiveness of policy mixes, especially as it relates to sustainable transition. However, a long-term strategic orientation appears to be critical, plus the path to achieve the desired objectives, and some appreciation of how instruments can be put to together to have synergistic impacts on each other. Policy learning in this dynamic context is also very important (Howlett et al., 2010; Rogge and Reichardt, 2016).

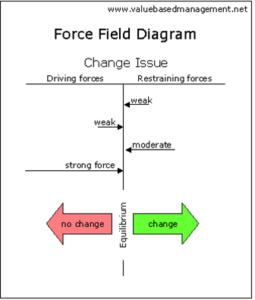

Lewin's (1947) Force Field Analysis is also useful in transition thinking because it helps to separate out the different elements affecting change (see diagram).

These forces occur at many scales and speeds, from very large natural, economic or cultural "events", many of which are rapid and unpredictable, to very localized and even individual phenomena that may build over time. A restraining case is one that blocks or restrains a desired development. A driving case is one that promotes or drives events toward a desired development. Change occurs when helping factors are maximized or introduced and hindering factors are minimized or removed. In general, governments are more likely at early stages of transition to provide some supports to driving forces for change, and are typically reluctant to restrict the restraining forces. This approach invariably results in limited progress until restraining forces are reined in at the same time as driving forces promoted. Very large and complex phenomena that appear quickly are typically the most challenging for governments to address.

Another key analytical transition question is the extent to which community and alternative initiatives are transforming the dominant system. Canada has many skilled food community organizers, who have used both classic and innovative approaches to community organizing (cf. Alinsky, 1989; McKnight and Kretzmann, 1993; Starhawk, 2011; Gibson - Graham et al., 2013; Desmarais et al., 2017) to effect primarily local level positive changes, of benefit to important but relatively small group of people. Transformation is an important consideration because it helps explain what alternatives are worth supporting, whether government intervention is desirable, necessary or problematic, or why governments resist taking action. A key raison d'etre of an "alternative" is to cause directly or indirectly the dominant to change something.

Change does happen at many levels and scales. Many in the "alternative sector" have hoped that a counter-hegemonic, or oppositional, approach (see Gramscii, 1992) that directly countered and refused to engage with the dominant system, would draw the population into different ways of being and thereby transform the dominant system. In the Canadian food system, this has not happened in significant ways, and although interest in alternatives has slowly increased, there are few indications of rapid adoption in the near term, in part because of resource and strategic limitations on the part of the alternative proponents. Although community-scale interventions are very important, this suggests there are certain limits to their reach that activists need be aware of. As a result, we cannot wait for counter-hegemony (some think of it as the "food revolution" or creation of food utopias, cf. Stock et al., 2015) to take hold, and more significant engagement with the dominant systems is required. And, as Gramscii (1992) suggested, the establishment can participate in the transformative process, even though they are embedded in the dominant approaches. Advocates for change must understand how to engage them in the transition by building strategic alliances with certain actors in the dominant system. In this way, the state "represents simultaneously the manifestation of corporate control over food and the possibility for progressive agri-food change" and "simultaneously a target, sponsor, and antagonist of social movements ...." (Barbosa and Coca, 2022:82).

A key question then is scaling up and out (Johnston and Baker, 2005) from the "alternative" to a more impactful role among the dominant processes, structures and systems. A key tension is scaling without compromising the values of sustainability, justice and health (Connelly and Beckie, 2016). Typically, successful small scale initiatives are slowly spread to other locations, each new version building on the learning from the other ones, yet somewhat unique to that location. Sometimes the projects increase in size as they spread, having more positive impact for more people. Often it is one organization or network animating, managing and funding the spread of successful initiatives. But at some point, the organization limits are reached, and other actors have to play a role in propagating the project. Often at this moment there is a breakdown in the scaling up and out process as few organizations, especially dominant ones, have the expertise or willingness (often feeling threatened by the alternatives, see next paragraph) to take on such functions. The founding organizations often do not think through this scaling process and are not prepared when reaching their own organizational limits, sometimes with failures related to financing and lack of management skill. Although for many projects, physical distribution infrastructure is important, the breakdown can be less related to lack of physical infrastructure and more about social infrastructure (cf. Connelly and Beckie, 2016). This reality, however, flies in the face of many government funding programs that only provide for hard infrastructure. But a presumption of this process is that enough initiatives can take hold in enough locations to have significant benefits for food system change. Given numerous scaling failures, at this point we have limited evidence that this will happen.

Typically, dominant systems that oppose alternatives have to be altered for scaling up and out to occur. From my experience and reading of the literature, there are multiple stages to this process of influencing dominant systems. Starting from a position where the dominant ignores the alternative, viewing it as a tolerable niche activity (some analysts refer to this as repressive tolerance, cf. Wolff, Moor & Marcuse, 1965; see also Laforge et al., 2017):

- At the first stage of influence, the dominant actors "bad mouth" the alternative, attempting to discredit it among decisions makers and the general public. Decision makers use various regulatory, programmatic and funding instruments to "contain" the alternative.

- At the second, they try to co-opt the alternative, often by buying it up. This is part of the "conventionalization" process, pulling alternatives back to the dominant system (cf. Mount and Smithers, 2014). Governments may present themselves as responsible for the successes of the alternatives.

- At the third, they try to look superficially like the alternative, again through purchase or marketing. This is a further stage in conventionalization. Governments will design "faux" programs that appear to support alternatives but really push them towards the dominant approaches.

- At the fourth, they partner with the alternative in some way, though the power dynamics of the partnership don't necessarily favour the alternative.

- At the fifth, firms start to revamp their supply chain to reflect the values of the alternative. Governments start to revamp programs and policies based on the successes and understanding of alternatives. This is when very significant transformation begins.

- At the sixth, firms start to dismantle themselves so that the restructured dominant system is actually the alternative (ultimate success and long term obviously). Government units are redesigned.

While there are many examples of the early stages of this process, there are only limited cases of the later stages. This framework is also used extensively on this site to explain the change process.

Finally, food systems are very complex and thus complex adaptive systems theory (see also Frameworks, General, Resilience; and Governance) is also pertinent to the change process. In this theory, change in complex systems often follow a particular dynamic path, though at different speeds, and often with interruptions and even reversion (before completion) to an earlier phase. This occurs in part because most complex systems are not currently managed as if they are complex. Our skills in complexity management are generally very weak. There is a "forward" phase characterized by a focus on efficiency and growth, with increasing degrees of control and structure for certain elements of the system. This rigidity leads to greater vulnerability and reduced capacity to adapt to stressors and perturbations. At a certain point, degradation and even collapse results which releases resources for re-organization, innovation and experimentation and the formation of new approaches, albeit vulnerable to failure or the poverty trap (limited capacity to gather the resources to scale up and out), particularly in the early phases of re-organization. If everything works well, initiatives can then move into the scaling up and out phase (for a summary as it relates to food system change in Northern Ontario, see Stroink and Nelson, 2013). In many ways, ideal policy change should be about integrating complexity management and adaptive capacity into the food system, in some cases hastening this cycle and in others protecting emerging promising alternatives from failure.

Of course, it's one thing to use transition frameworks to conceive of and organize strategies, and another thing to then advocate for their implementation. See Get Started, What does an effective policy advocate do for more on that theme.

Some argue that even the ambitious agenda set out using the ESR framework will be too slow to prevent ecological and social collapse (cf. Bendell, 2018). I would be delighted if change happens more quickly than I propose, possible if we collectively seize the need for rapid transformations as happened in WWII (see Goal 2, Demand - supply co-ordination, Lessons from WWII).

Endnotes:

[1] The term Efficiency in the ESR framework should not be seen as equivalent to traditional economic interpretations of efficiency. Note that there are also many policy transition frameworks, see MacRae and Winfield (2016) or Frameworks for a review pertinent to food policy themes.

[2] Although there have been amendments to federal-provincial powers in earlier periods prior to patriation of the Constitution, since 1982, because of the amendment formulas, amendment debates have been fractious and the types of amendments that would be pertinent to those discussion, largely unsuccessful.