Much of the adoption literature focuses on the need for values changes on the part of producers. Certainly earlier adopters of organic displayed very values-driven motivations. Our presumption here is that, while valuable, values changes among next wave adopters will need to be provoked by systemic interventions that create new incentives for adoption. In this regard, for many producers, the most critical elements to overcome barriers have been financial support for the transition, help with upstream supply chain organization and marketing, decent prices, clear demand signals, and access to transition advisors (Padel and Foster, 1999).

Setting the level of payment for transition

Direct payments to producers for transition to environmental practices have been criticized in the past because they are difficult to target to those who will generate significant environmental improvements from their funded actions. Evaluations of programs in the US and Europe have found that some are both too expensive and only really taken up in less intensive agricultural production areas where the environmental problems are not as acute (Dobbs and Pretty, 2001; Batie, 2002). Other complicating factors include:

(1) that many farmers and other actors may be contributing to the problem;

(2) that since much of the pollution is non-point source, it is difficult to observe and measure impacts and their sources;

(3) the wide variability in farm types and their economic and ecological conditions;

(4) the unpredictability of negative natural events;

(5) the need for many farms to improve their environmental management to achieve improvements (Batie, 2002).

All these complications can mean considerable costs for government administering the program.

If only one environmental target is sought, then it is more efficient to design a program specific to that. But since many of the most significant environmental problems in agriculture are not related to a specific farming activity, then combinations of changes, or system alterations, are usually required. If multiple environmental improvements are sought, then targeting farms participating in multidimensional environmental enhancements is a much more efficient allocation of policy and program resources then designing programs around each specific environmental target (Batie, 2002; Dabbert, 2003). Organic farming generates multidimensional environmental improvements and direct payments for organic farming mitigate some of these programme design problems. However, there is little empirical evidence available to support this, in part because evaluations must assign costs and benefits according to the multiple environmental benefits that result from organic farming, an admittedly difficult task. One study (Jacobsen. 2003) assigned all the costs of organic farming support to one environmental target, suggesting that organic farming support schemes are therefore inefficient. A more appropriate approach would be to examine the main benefits that result from organic farming, for which there is significant scientific support and then determine programme effectiveness.

European states have been supporting farmers through organic adoption by providing payments, usually on a per area or per animal basis, through the transition period. The rapid increases in organic acreage experienced in Europe owe much to the existence of organic aid schemes (OECD, 2003). Over 80% of organic growth in Europe occurred reasonably quickly after implementation of definitional and control measures and support schemes (Stockdate et al., 2001). According to Lohr (2001), “The ability of EU farmers to rely on direct payments for conversion to and continuation of organic enables greater risk-taking in enterprise mixes, including high-value, high-risk crops, faster adoption of practices that require land-use adjustments that improve yields, and broader extensification of organic acreage that increases total output.” Comparing the US and Europe, she found that while dramatic growth rates were the result of the introduction of direct payments in the EU, during the same period, the number of organic farmers and acres actually declined slightly in the US where governments have relied primarily on market mechanisms and some grants.

A significant challenge has often been finding the right level of support. A comparative assessment of direct subsidies in Canada and New Zealand (Bradshaw, 1995) indicated that the appropriate level of government support is not so high as to encourage unsustainable financial dependency, yet sufficient to compensate for the market’s inability to reward farmers for being good environmental stewards. Similarly, the European Commission has tried to find levels that do not substitute for the market’s contribution to income generation, but also recognize the broad societal benefits that result from farmer’s delivery of environmental services - benefits that can not necessarily be recouped from the market place. When farmers are learning through the transition process, the benefits go beyond their own finances. It is for this reason that governments began to support the transition in the late 1980s (Lampkin, 1996). The intention, consequently, was to have the payment schemes be neutral - they would replace revenue foregone because of the adoption of environmental measures. The EC believed that small incentives beyond this should only be paid to increase uptake to reach a stated environmental objective (European Commission, 1999). Lampkin (1996) concluded that the payment levels should take account of the costs of environmental improvements farmers are expected to meet, the resulting environmental benefits, the costs of conversion and the potential for savings in public expenditures.

In earlier programme periods, levels of payment in the EU were not sufficient to encourage arable, horticulture, pig and poultry producers. The most common conversions in most countries were low to medium intensity dairying (Lampkin, 1996). This suggested that those systems reliant on pesticides were insufficiently encouraged to reduce the application of pesticides. In the late 1990s, Austria (335 ECU/ha/yr for cereals) and Finland (365 ECU/ha/yr for cereals), with the highest payment rates also had the highest uptake, whereas the low rates in the UK (82 ECU/ha for all organic crops) proved to be less attractive (Lampkin, 1996). Certainly, enhanced uptake in the UK was associated with programme and payment improvements in the early 2000s. The responses of farmers to both schemes, associated with programme changes, clearly exceeded projections, and funding was exhausted within six months (rather than 2 years as originally projected). When the programme was altered and reopened, the take-up rates presented the largest wave of conversion to organic farming methods in the UK to that point, increasing the organic area 12-fold from 1997 (Centre for Rural Economics Research,, 2002). On so-called improved land, a tripling of per hectare payments in the first year (to 225 £/ ha) and a near doubling in total payments over 5 years (to 450 £) accounted for the rapid increases (Centre for Rural Economics Research, 2002:Table 1.1). On average, payments ranged from 190 ECU/ha/yr for cereals, 210 ECU for grassland, 280 for vegetables and 540 for fruit trees. Conversion rates in livestock operations were particularly sensitive to available payments. Rates have since been altered again (see Table 2 in Stolze and Lampkin [2009] for 2004/05).

MacRae et al. (2009) in an examination of programme and policy incentives to encourage organic adoption to 10% of conventional production in Ontario set payment levels at 10% of foregone gross revenue. This level was chosen to be slightly lower than Europe, where such payments have typically ranged from 15 - 20% of foregone revenue. Using a different indicator, Offerman et al. (2009) found that EU payments in the mid 2000s amounted to 3-17% of gross output, for both existing and converting organic farmers. Zander et al. (2008) concluded that in Western Europe, payments amounted on average to 4-6% of gross output and 10-30% of farm family income plus wages. This is less than other non-organic payments.

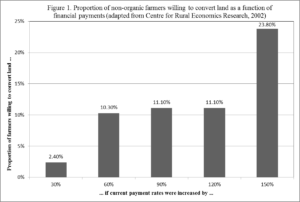

Based on Swedish data, and comparing a situation with no direct payments to provision of direct payments for conversion, direct payments were estimated to induce a 27% increase in farmers undertaking a conversion (Lohr and Solomonsson, 2000). Arfini and Donati (2013), using positive mathematical programming and cluster analysis with Italian data, found that subsidy payments of 150 Euros / ha for organic cereals were more effective than price premiums at increasing adoption. However, the stimulation of adoption was very dependent on farm and spatial characteristics, with the most significant uptake amongst small to medium farms in regions where organic production is already at a higher level. Offerman et al. (2009) found that at least 56% of Western European farmers felt that organic farming payments were important or very important to the decision to adopt and 76% of Eastern European farmers felt similarly. The Centre for Rural Economics Research (2002), assessing the lower rates of payments in the UK at that time, found that, ”66% of non-organic farmers said they would consider switching if the OFS grants were increased. Our findings suggest that an aid package that offered roughly twice what is currently available would attract 7.8% of conventionally managed land area over to organic production, bringing the total up to just over 11%.”In their analysis, 34% of conventional producers would not convert whatever the level at which financial incentives were set. The Centre for Rural Economics Research data suggest that a further 10% of conventional farmers would convert with rate increases of from 60-120%, but that a significant jump to over 20% would require a 150% payment increase (Figure 1).

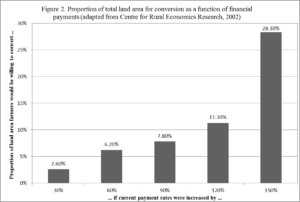

Figure 2 “... shows the proportion of the total land area that farmers would be willing to commit to organic production at successively higher grant rates .... This function can be interpreted as a supply curve for organic conversion, where ‘supply’ is measured in terms of the share of organically managed land.... An aid package offering roughly twice the amount currently available (90% more) would attract 7.8% of the conventionally managed land area over to organic production, bringing the total up to just over 11%. Austria has an aid package similar to this and has roughly 8% of its agricultural land area under organic management.” (Centre for Rural Economics Research, 2002)

The Centre for Rural Economics Research (2002) study also drew some other conclusions to inform the construction of our ABM:

- A quarter to a third of farms would have converted without the presence of the scheme, across the main enterprise types

- Reversion to conventional production also had to be considered. They estimated “that for every 100 farmers who enter the Scheme, 79 will retain organic management after 5 years, but only 53 of these can be attributed to the operation of the Scheme, since 26 would have converted anyway. In other words, 79% of the initial benefits of conversion continue to be delivered after 5 years, but only 53% can be attributed to the Scheme.”

- There is an augmented impact the more farms convert in an area: declining unit marketing costs; improved information dissemination; positive network effects; positive learning effects.

Certainly higher payments contribute to more rapid uptake, but many complications related to how schemes were administered, eligibility rules, acceptable practices, and changes in access to other non-organic schemes associated with participation in organic schemes. In many cases, the loss of access to other schemes had significant negative impacts on organic uptake (Lampkin 2003). These kinds of complications, however, do not exist in Canada where programme payments are far less robust than in Europe. Interestingly, a survey of Ontario sub-watersheds, including the one modeled in this project (Filson et al. 2009), found that 90% of farmers were interested in receiving payments for ecological services.

Conversion advice

Formal advisory services, financed by the state, are a reasonably recent development, with funding generally beginning in the 90s although some private institutes offered services earlier. Several states in Europe and the US federal government have funded such services. The importance of advisory services is generally underreported in the literature (Lamine and Bellon, 2009a), but it appears that they can provide critical information and support during key moments in the decision to go organic and the implementation of the conversion process. Their success, however, is particularly dependent on the quality of the conversion advisors and the degree to which services are provided at low or no cost to farmers.

In Europe, advisory services operate in a more than a dozen nations and typically offer combinations of the following programs:

- telephone helplines

- information packages

- farm advisory visits

- courses

- handbooks and manuals

- farmer mentoring programs

The service in Wales was reasonably typical when created. It was first funded by the Welsh government from 1996 and operated by the NGO The Soil Association and the Organic Centre Wales, University of Abersytwyth. It offered three main services: a telephone help line, a conversion information package, farm visits (2 free ones, the first providing an overview of conversion, the second dealing specifically with the circumstances of the farm), carried out by staff of both non-profit and governmental agencies. Farmers wishing more support for conversion paid directly for additional services. Through revisions to the Rural Development regulation, the EC helped defray advisory service costs for eligible farmers (CEC, 2002).

An evaluation of the Organic Conversion Information Service (OCIS), Wales (1996-2001) (Organic Centre Wales, 2001) revealed that most participants had limited to fair knowledge about organic farming when they contacted the service, and that most farmers followed through from initial telephone call to preliminary visit, to second visit. There was generally high farmer satisfaction with the service. Of the 2480 farmers who had called the service in a 5-year period, 56% had the first visit, 30% the second, and 11% had gone on to convert. 61% of farmers surveyed had decided to convert. Of those, 56% said the service was very or fairly instrumental in their decision. Those who decided not convert to organic agriculture cited larger issues around the stability of organic markets and costs as barriers.

A review of the English OCIS in 1997 drew similar conclusions except that the emphasis on marketing information did not emerge. The UK evaluation suggested that information alone is insufficient to advance the transition, finding no connection between information and willingness to convert (Centre for Rural Economics Research, 2002). However, providing information in the context of a free organic conversion information service appears to shift the equation. The study found that such a service launched in the UK was an important source of pre-conversion information. Some French studies, however, contradict the UK results. In one analysis, 50% of producers reported that information deficiency was a significant obstacle (Santereau, 2009). Conventional producers will often be more comfortable getting advice through conventional channels with which they are familiar, speaking to the need to integrate organic advice into regular services (Sautereau, 2009).

A 1953-1996 duration analysis (Burton et al., 2003) in the UK revealed that, for organic adoptions in the horticultural sector : (i) the enhanced environment associated with (ii) the creation of a formal conversion advisory service, combined with (iii) strong environmental concerns and (iv) links with other farmer groups, created a higher likelihood of adoption. Interestingly, despite the economic nature of this analysis, the authors found that non-economic forces appeared to be more powerful for the adoption process than economic ones. Age and education, farm size and non-farm income did not appear in the earlier, less supported periods, to be significant. But gender was important, with females more likely to adopt than males. Burton et al (2003:48) note that “[i]t may be that the longer the producer continues as a non-organic farmer, the greater are the costs associated with conversion to an organic system.”

Attitude of neighbours and institutions

The transition to new systems is a particularly important stage, and according to Dobbs and Pretty (2001), several factors have proven important in European cases:

- good local pioneers who could demonstrate that their sustainable farming works and pays

- effective consultants and extensionists, providing support, economic data and technical advice (see also Kroma [2006] in the US)

- those engaged in the transition deliberately stayed in touch with conventional farmers so as to prevent the emergence of ideological divisions; this has also proven important at the larger organizational level where the transition to organic farming has been smoother when good relations existed between conventional and organic farming groups (Mickelsen et al., 2001).

- farmers organized in groups to study and carry out implementation (Kroma, 2006). Danish research has shown that farmers organised into crop protection groups and who access information from extension systems have the greatest reductions in pesticide use (both doses and frequency) and input costs (Just and Heinz, 2000). In the mid 1990s, there were 621 crop protection groups in Denmark with 4,300 members (1 in 7 of all full-time farmers).

- new partnerships between farmers and other rural stakeholders, as regular exchanges and reciprocity increase trust and confidence, and lubricate co-operation.

The UK evaluation (Centre for Rural Economics Research, 2002) revealed that neighbouring farmers become more sympathetic to organic agriculture after a farm conversion. In this assessment, the number of sceptical farmers nearly halved, though it was not entirely clear how much of this response was a general trend rather than a product of the organic transition programme. Public support for organic farming did, however, create more favourable impressions among conventional producers, with 36% favourably influenced by government support programmes and 18% indicating they were considering undertaking transition. Seven percent of organic farmers surveyed reported that their non-organic neighbours had decided to convert after viewing their successes, and 36% said that their neighbours had become more sympathetic to organic farming. Thus, it would appear that the combination of public programmes and successful transition by neighbours does have an impact on other farmers (see also Parras-Lopez et al., 2007).

There is some similar evidence from French and Spanish studies that official support for organic farming helps reluctant producers decide to convert to organic (Defluaunt et al., 2002; Parras-Lopez et al., 2007; Sautereau, 2009). Especially for those farmers not willing to work directly with a peer group, official supports help with social legitimation (Sautereau, 2009:198). One study found that 21% of producers with a transition plan claimed that poor acceptance by neighbours was a limitation on their transition. The support of official entities helped them move forward. Support of regional bodies was important, especially when linking organic transition is part of larger effort to protect the environment (Santereau, 2009).

Burton et al. (2008) suggest that if other farmers see the locale-specific symbols of “good farming” in the adoption of new approaches, they will view the changes more favourably.

The complex interactions of multiple driving forces with barriers are difficult to tease apart. This is one area where complexity modelling, such as agent-based modelling, can make a contribution. For example, Kaufman et al. (2009) used ABM to examine the interplay between subsidies, social influence, marketing support and the presence of conversion advisors for conventional farmers transitioning to organic production in Latvia and Estonia. They gathered survey data to empirically derive formulas for the model. A key part of their data collection was understanding farmers’ perceived approval or disapproval by others in their network (or important others) for adopting organic farming. This measure incorporates influences of marketing potential, affordability of adoption and the influence of subsidies. In the Latvian case, they found that social influence alone had little effect on adoption rates, but that there was a significant additive synergistic effect between social influence and subsidies, including making producers responsive to changes in others’ opinions. Farm advisors also increased adoption rates, but did not interact synergistically with social influence parameters unless the farm advisors had talked with 75% of the non-adopters. Similar results were found in Estonia, except that the presence of conversion advisors was a more significant factor, more so than subsidies which had a relatively minor effect on adoption.

The differences between the two countries are attributed to the significantly different conditions of organic farming. The Latvian study area is a close-knit farming community attempting to use rural development strategies to make a living from agriculture in the region. The Estonian one was more focused on tourism, and the move to organic was associated with lifestyle choices and supportive environments for the tourism industry. For conventional farmers in Estonia, shifting to organic did not seem economically viable, explaining why subsidies were less an incentive than social relations and farm advisors. In Estonia, the authors concluded, policy makers should not increase subsidy levels but rather focus on social supports if they wanted to enhance adoption. Investing in subsidies and supply chain infrastructure would appear to be more promising in Latvia. Both these regions, relative to others in the industrial world, do not require difficult on-farm biological transitions because, since the early 1990s, the cost of synthetic inputs has restricted their use.

Parras-Lopez et al. (2007) found a stronger network “contagion” effect in the marginalized olive growing areas of Spain, compared to the high-yielding ones. This explained, in part, much higher organic adoption rates in those low-yield, marginal regions. However, they suggested that better integration of this contagion effect with information transmission and financial supports would accelerate the process.

In Germany, Schmidtner et al. (2012) found that counties with high concentrations of organic farms had significantly positive impacts on conversions in other counties. A 1% increase in organic farms generated a 0.44% increase in the neighbouring administrative unit.

Support for upstream marketing

Most EU-15 countries provide support for market analysis, marketing, supply chain infrastructure development and public procurement projects, either directly from the state or through financial support of third party organic marketing schemes (Stolze and Lampkin, 2009). Sautereau (2009) reported that support for upstream marketing was very important for new converts. Producers will design their transition based on such diverse characteristics as how much yield loss they can tolerate, how difficult the labour is, by quality of life, by handing off commercialization to someone else, or by having more independence to follow their own marketing strategy.

There is some evidence that co-operative structures can facilitate the transition from conventional to organic, especially when conditions suggest a conventional approach cannot be sustained and where the co-op already contains a mix of organic and conventional producers (Lamine and Bellon, 2009b).

Schmidtner et al. (2012) found that the existence of organic food stores was strongly correlated with the existence of a proximate organic production area. Lobley et al. (2009) found that organic farmers were much more likely to be integrated into supply chains to capture value and closer links to customers than conventional ones, with a much higher percentage running trading operations and on-farm processing.