(adapted from work conducted by Julia Langer, Vijay Cuddeford and Rod MacRae for WWF Canada during the early 2000s and from MacRae et al., 2012)

The efficiency stage addresses minor amendments to programs. Unfortunately, much of the IPM infrastructure put in place in the 1980s and beyond has been dismantled. Many provinces had significant numbers of IPM extension specialists. There were regular events for growers, grower IPM manuals were available, public and private scouting services existed and networks of researchers and extension specialists met regular through "expert committee" processes to share research and develop priorities. The federal research system had numerous scientists working on IPM and it was a research funding priority. Some commodity associations were also involved in sector wide IPM adoption programs.

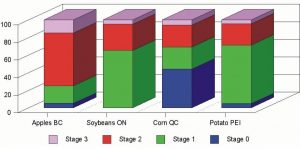

A World Wildlife Fund (2003) analysis indicated progress had been made on IPM adoption in certain crop - region combinations, following a 4 point scale, where 0 indicated no progress, 1 was early stage IPM adoption, 2 indicated significant advances, and 3 a stage where few synthetic pesticides are employed and reliance on pesticides is dramatically reduced (see figure).

IPM adoption by stage and region-crop combination (WWF, 2003)

Unfortunately, provincial departments of agriculture began to cut back their extension services, including IPM supports such as specialists and pest forecasting systems. IPM manuals were not updated, and field days limited. Federal research programs were increasingly tied to industry contributions and IPM was not a favoured area for research since it did not have a well funded business constituency as does pesticide manufacturing and other technological approaches to pest management. Commodity groups, such as the Canadian Horticultural Council and the Canola Council, stepped somewhat into the breech, sometimes with short term federal grant money but this too could not be sustained after a few years. The expert committees on IPM were disbanded in 2006, part of government budgetary retraction. These retractions have not been unique to Canada, part of global forces and processes limiting IPM implementation that have called into question both the influences of the pesticide industry and whether decision makers are truly serious about reducing pesticide harm (cf. Deguine et al., 2021).

With the passing of the 2002 Pest Control Products Act, the federal government shifted its focus to pesticide risk reduction, a narrower conception of pest management than IPM. Because the federal government has seen its primary function as pesticide registration, this approach was probably viewed as jurisdictionally coherent, even though a limited conception of federal authority on a significant environmental issue that was being addressed very inconsistently among the provinces.

The Pesticide Risk Reduction Programme was created in 2003 by Agriculture and Agrifood Canada (AAFC) and the Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA). It was structured as a joint initiative, with a new operating unit within AAFC (the Pest Management Centre). The design was partly influenced by significant consultation with industry and a few ENGOs, including WWF. It was set up to support sectoral pesticide risk reduction strategies (expanding on the earlier initiatives of the PMRA Alternatives Office), and to facilitate registration of reduced risk pesticides.

To implement this new agenda, the programme gradually:

- set up extensive mechanisms for identifying pesticide registration priorities, particularly among minor use crops, involving representations from industry, farm organizations, and the provinces/territories

- established mechanisms based in the IR-4 programme in the US to conduct testing that would speed up the registration process[i]

- commissioned numerous “state of IPM” commodity reports

- worked collaboratively with commodity sectors on risk reduction programmes and attempted to find innovative ways to support their implementation

- Created linkages with the AAFC and provincial research communities to advance understanding of IPM and related issues

- commissioned a study and workshop on establishing a national coordinated programme to advance IPM adoption

Although having more reduced risk pesticides is helpful, it's only a minor reason why farmers don't adopt environmental systems (see Goal 5, Sustainable Food). Without systems adoption, only minor environmental improvements will be generated (see Instruments). The failures of a reduced risk approach have become evident.

- Most of the resources are devoted to registering minor use pesticides, only some of which are legitimately reduced risk, and most of those registrations are label expansions, i.e., pesticides already approved on some crops are approved for more crops. Ironically, many of the registered products or label expansions are not likely to last unless used within an IPM context, but supports for IPM adoption are not part of the programming.

- The sectoral Reduced Risk Strategies have not been properly supported. Because there is not a coordinated IPM program at a national level, when a commodity group identifies needs, they have to cobble together resources from a variety of places, including their own membership. The result has been spotty implementation of identified plan elements.

- The IPM commodity reports have been more assessments of chemical controls than the state of pest management. The authors, for the most part, have not demonstrated a clear understanding of the elements of IPM.

- A report and workshop on establishing a coordinated national IPM system, that provided specific details of how multiple actors could contribute, was poorly received and none of its elements have been implemented. The proposals required a level of collaboration that has yet to be seen in pest management.

Given this history, a return to 1980-level interventions is unlikely. The most vibrant, but limited, dimension of the current regime is the Minor Use program co-ordinated by AAFC's Pest Management Centre, and now part of the Canadian Agricultural Partnerships. The program identifies, with the participation of a wide range of regional, provincial and national actors, priorities for minor use pesticide registration, products or expanded uses of existing products that pesticide manufacturers do not consider economically viable if they have to undertake the research and registration procedures because the product will only applied on a small acreage. The R&D and registration costs are now so significant that manufacturers are really only interested in products with large sales potential. This speaks to a significant problem in the market place, that scale increases and input sector concentration have rendered small to medium acreage crops non-viable from a corporate perspective. To compensate for these dysfunctions in the market, the state conducts field and greenhouse trials and laboratory analyses to produce the required product efficacy, crop tolerance, and pesticide residue data, and then drafts the regulatory submissions to PMRA for the registration of new minor uses of pesticides under the regulations of the Pest Control Products Act.

The problem with all this is the ongoing focus on "products" to solve problems that are really about farm design and management. As such this initiative continues farmer reliance on synthetic pesticides when the focus should really be on pest prevention, fundamental to Integrated Pest Management. Registration of low - risk pesticides should be a complement to pest prevention strategies, not the main objective.

Consequently, the program needs to modified to set an explicit focus on IPM rooted in agroecology that progressively leads to system redesign, sometimes referred to as Agroecological Crop Protection (Deguine et al., 2021). A priority setting process and network already exists, involving grower organizations, provincial minor use pesticide coordinators, manufacturers and federal researchers, with advice from an equivalent program in the US. The network would need to be expanded to include regional IPM expertise. The priority setting process would be begin with pest prevention requirements, and once those were identified, would supplement the tool box with minor use pesticide priorities. Coordination could still be provided by the PMC, and funding provided as part of the Canadian Agricultural Partnerships. It would shift the kinds of trials conducted as the focus would not just be on pesticide efficacy and crop tolerance. It would engage many of the federal and provincial entomologists, pathologists and weed scientists who have had difficulty funding their ecological research. The remaining provincial IPM extension specialsts would also be involved to help identify priorities and knowledge transfer strategies. It would also intersect with the sectoral Pesticide Reduction Strategy process, as those sectoral groups would also play a key role in identifying priorities and resources for implementation. As indicated earlier, manufacturers would participate because they know that the longevity of their products is often tied to grower IPM adoption.

Endnotes:

[i] The IR4 programme, or Interregional Research Project 4, has been a primary mechanism to bring to commercialization new pest management products for specialty crops in the US. The IR4 develops field residue data and other performance data on chemicals that the pesticide industry will not normally develop on its own because the limited size of the market for the product.