Jurisdictional issues and government responses (research and analysis by Kennedy Halvorson)

Given the many forces affecting wildlife and habitat, this is a multidimensional jurisdictional problem. The federal and provincial governments have numerous independent and collaborative responsibilities, and these are spread across multiple departments. Some relate directly to species, others are related to the forces having an impact on them. Many of these forces are discussed in other change areas of this site.

Although many federal and provincial statutes make mention of biodiversity conservation and address related matters, no statutes are specific to an integrated approach, except to some extent Nova Scotia's aspirational 2021 Biodiversity Act which has more integrative elements than other statutes. As a result, interventions are primarily policy and programmatic, primarily under the aegis of the Canadian Biodiversity Strategy adopted in 1995, and actions are dispersed across multiple departments at all levels. However, no provinces currently have active biodiversity strategies to complement the federal one. Six provinces/territories have had strategies/action plans that appear by 2020 to have expired, although some of them may be under review from which an updated strategy will emerge. The NS act is too young to have produced a strategy and the original bill was weakened as it progressed through the legislature, leaving out many of its critical regulatory dimensions (see Mitchell, 2021). Some sub-provincial regions also have had strategies. Eighty-nine percent of Canada's ecological assets are primarily controlled by the provinces which, when added to constitutional realities and the focus on land use for biodiversity conservation, limits the scope of potential federal interventions and contributes to fragmentation of response (for a detailed breakdown of federal and provincial biodiversity conservation instruments, see Ray et al., 2021).

Species at Risk

Of particular importance for the discussion in this change area is the federal Species at Risk Act. In 1992 Canada signed and ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity, a multilateral treaty with three guiding ambitions: “(1) The conservation of biological diversity, (2) The sustainable use of the components of biological diversity, and (3) The fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources” (Secretariat of the CBD, 2012). This commitment has shaped national biodiversity policy in Canada and helped produce in 2002 the Species at Risk Act (SARA). It asserts that Canadian wildlife and ecosystems have “value in and of itself” (SARA, 2002, pmbl.), which the government is committed to conserving through legal protections. The federal government sees SARA as part of a three-part federal strategy for the protection of wildlife species at risk, the others being the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk and the Habitat Stewardship Program for Species at Risk which focuses on regional community and ecosystem level projects.

The ultimate purpose of SARA is to:

“Prevent wildlife species from being extirpated or becoming extinct, to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity and to manage species of special concern to prevent them from becoming endangered or threatened” (SARA, 2002, sec. 6).

Three federal agencies are ultimately responsible for implementing SARA:

-

- Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) generally manages all SAR as well as migratory birds,

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) is responsible for all aquatic SAR, and

- Parks Canada oversees SAR in national parks and historic sites.

The ministers of these agencies form the Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council, along with relevant provincial ministers. This council has designated the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), an independent advisory panel, to identify Canadian wildlife at risk and produce status reports on each species. After receiving a COSEWIC report, the ministers in the Council then decide whether a species is eligible or not for listing under SARA. Once a species is listed under the SARA as threatened, endangered, or extirpated, the government has a duty to create a recovery strategy that outlines the short and long-term aims to recover the species at risk, followed by an action plan which details the actual measures and projects to be undertaken to achieve those aims. Recovery strategies should be completed within one to two years of the species being listed, and include information on the species and their needs, threats to survival, critical habitat, information gaps, and a proposed timeline for the action plan. The action plan that results is a dynamic document that further clarifies critical habitat related to the species, identifies activities that may negatively affect it, and proposes measures to protect the habitat. The document also outlines steps to implement the recovery strategy, and evaluates the socio-economic costs and benefits of conserving the species.

Seven provinces and territories also have species at risk statutes. Ontario's Endangered Species Act is notable for having been weakened in 2019 to facilitate development processes. Alberta's measures are also widely criticized for favouring extraction industries over species at risk (Ray et al., 2021).

Some provinces have species at risk incentive programs that are connected to the Canadian Agricultural Partnerships (CAP) through the Environmental Farm Plan process, but not necessarily funded through that mechanism. Ontario has a Species at Risk Farm Incentive program funded through the Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks Species at Risk Stewardship Program. Eligible producers must have an EFP and can receive funding on a cost share basis for a wide range of best management practices providing direct and indirect benefits, and for monitoring, up to $20,000 maximum for 2021-22. Funding was allocated on a first come first serve basis which implies no targeting. The MULTISAR program of southern Alberta, with multiple partners including the provincial government, and funding from ECCC, is a voluntary program focusing on habitats for Species at Risk.

Protecting farms from wildlife and invasive species

Wildlife compensation programs

The provinces, in addition to supporting federal work on species at risk, also have regimes to protect farmers from wildlife, particularly damage to crops and animals and disease spread from wild to domesticated animal populations. Typically there are 4 approaches - eliminating the offending organism, prevention (often habitat modification), changing human behaviour, and living with it to some degree (compensation fits into the latter category). Eliminating the offending organism (traditionally by shooting, trapping or spraying) is often ecologically the most problematic. Some provinces (e.g., Alberta's Carnivores and Communities Program) provide funding to help farmers reduce food sources on farms in areas frequented by wildlife. Properly designed, wildlife compensation programs can be seen as strategies to protect biodiversity by permitting a level of co-existence but the history of these programs is not consistent with this view. They have emerged more out of a "control of nature" attitude. But more positively, they can also improve attitudes towards wildlife, and reduce the risk of further injury to humans and livestock when employed instead of physical management tools like traps or hunting (Wagner, Schmidt, & Conover, 1997).

In Canada, two territories and eight provinces have some sort of program in place to compensate affected parties for damage to either crops, livestock, or property (Table 1). Some also offer compensation for the cost of wildlife prevention methods like fencing or guard dogs. The costs of these programs are shared by the provincial governments and the federal Wildlife Compensation Program (separate from AgriInsurance). The goal of the Wildlife Compensation Program is to provide “compensation primarily for small and medium-sized losses resulting from wildlife damages to crops or predation of livestock”; how and when this compensation is distributed is under the discretion of the provinces and territories (AAFC, 2017). The schemes vary in coverage, but typically, the process of applying for compensation goes as follows:

- The affected party notifies the appropriate provincial or territory office within the designated timeframe.

- They are evaluated to see if they qualify for compensation, which is typically dependent on the type of livestock or crop affected AND species of wildlife suspected to be responsible.

- If deemed eligible for compensation, the affected party may pay an appraisal fee and is also responsible for preserving evidence of damage (carcass, photographs, crops, veterinary bills, etc.) until an investigator can come to confirm that the damage was incurred by wildlife AND that the affected party has employed best management practices to prevent wildlife damage.

- Once confirmed by the investigator, the affected party is responsible for properly disposing of the evidence. Compensation is then determined based on a few factors, including time of year and size of damage to crops, or age of livestock.

- If denied compensation by the investigator or unfairly compensated, the affected party can appeal the decision to the provincial/territory office.

There are some stand-out differences in compensation programs available; in both Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador, compensation is only available to parties who have insurance through specific providers, not through the Wildlife Compensation Program. Coverage is also absent in the Northwest Territories. Ontario provides no compensation for crop damage of any kind, and Quebec only covers crop damage done by a few waterfowl species. Provinces and territories have the authority to determine what species qualify, basing their decisions of the availability of wildlife damage mitigation strategies active under their jurisdiction (AAFC, 2017). Some programs do not cover all of the damage costs, with affected parties in provinces like Alberta only eligible for compensation of up to 80% of the value of damage. The timeframe for which affected parties must report damage also varies; in Ontario, damage must be reported within 48 hours, while in Manitoba and New Brunswick allow 72 hours, and territories like the Yukon have no specific timeframe other than when damage is noticed.

Provincial programs also have variable coverage for game farms. In most provinces, rules on endangered and big game hunt species are addressed differently than what is offered in these programs.

| Table 1: Summary of Wildlife Compensation Program as applied by Provinces and Territories | ||||||

| Province/ Territory | What does the province/territory offer compensation for? | Types of crops, poultry, livestock, and other animals that qualify for compensation: | Eligible species of wildlife for damage to crops, poultry, livestock, and other animals: | Reimburse/compensate for wildlife prevention or anti-predation costs? | ||

| Crops | Animals | Property | ||||

| Alberta | ✔️ | ✔️ | ❌ | Crops: unharvested hay crops, swath and bale grazing (until Oct. 31st), stacked hay, haylage (pits/tubes), unharvested cereal, oilseed, special and other crops that can be insured under AFSC insurance and Straight Hail Insurance programs. Swath, bale, and corn grazing (until Oct. 31st), silage (pits/tubes)Livestock: cattle, bison, sheep, swine and goats |

For damage to crops: antelope, bear (only annual crops), deer, ducks, elk, geese, grouse, moose, mountain goat, mountain sheep, partridge, pheasant, ptarmigan, sandhill cranes

For damage to livestock and poultry: wolves, grizzly bears, black bears, cougars, eagles

|

✔️ - An agricultural producer is eligible for compensation from ungulate damage:

|

| British Columbia | ✔️ | ✔️ | ❌ | Crops: grass, cereals, legumes, grain, fine seeds, oilseeds, pulse crops, any crop eligible for crop insurance

Livestock: cattle, sheep |

For damage to crops: bison, bears, cranes, deer, elk, moose, mountain sheep, waterfowl

For damage to livestock and poultry: coyotes, wolves |

❌ |

| New Brunswick | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️* only damage to bee related equipment is eligible

|

Crops: apples, apple trees, strawberries, wild blueberries, cranberries, raspberries, grapes, potatoes, seed potatoes, barley, oat, wheat, mixed grain, field corn, field peas, soybean, canola, processing carrots, broccoli, beans (green & wax), brussels sprouts, cauliflower, cabbage, green peas, fresh carrots, onions, parsnips, rutabagas, winter squash, pumpkins, sweet corn

Livestock: cattle, sheep, goats Other animals: bumble bees, honey bees, leafcutter bees |

For damage to crops: raccoons, woodchucks, gophers, porcupines, skunks, white-tailed deer, moose, black bears, beavers, crows, blackbirds, ravens, ducks, geese, birds of prey, whimbrels, seagulls, wild turkeys, and wild pheasants

For damage to livestock and poultry: black bears, bobcats (lynx), foxes, coyotes, cougars, wolves, ravens or crows; and any birds of prey For damage to beehives, bee colonies and/or bee-related equipment: skunks |

❌ |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | ❌ | ❌ - can receive compensation through Livestock Owners Compensation Board Insurance | ❌ | N/A | N/A | ❌ |

| Northwest Territories | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | N/A | N/A | ❌ |

| Nova Scotia | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️* only damage to bee related equipment is eligible

|

Crops: apples, pears, barley, beets, broccoli, brussels sprouts, cabbage, canola, carrots, cauliflower, celery, corn, early potatoes, egg plants, fall rye, feed wheat, field cucumbers, field tomatoes, fresh beans, grapes, green onions, highbush blueberries, kale, lettuce, lowbush blueberries, melons, milling wheat, oats, onions, parsnips, peppers, potatoes, pumpkin, radishes, raspberries, rutabaga, soybeans, spinach, strawberries, summer squash, summer zucchini, summer turnips, sunflowers, triticale, winter squash

Livestock: cattle, sheep, goats Other animals: bumble bees, honey bees, leafcutter bees |

For damage to crops: beavers, birds of prey, black bears, blue jays, coyotes, crows, moose, rabbits, raccoons, ravens, robins, seagulls, skunks, starlings, waterfowl, white-tailed deer

For damage to livestock and poultry: birds of prey, black bears, coyotes, crows, foxes, ravens, wild cats |

❌ |

| Nunavut | ❌ | ❌ | ✔️ | N/A | For damage to property: no specific species, just wildlife in general | ✔️ - Residents and recognized non-profit community groups of Nunavut who wish to take measures to prevent and reduce wildlife damage to their personal property are eligible to apply for funding in the Wildlife Damage Prevention Program. The local Conservation Officer assists in choosing the most suitable and cost-effective prevention methods |

| Manitoba | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️* only damage to bee related equipment is eligible

|

Crops: wheat, oats, barley, flax, rye, canola, rapeseed, mixed grain, buckwheat, triticale, tame mustard, field peas, corn, sunflowers, edible beans, lentils, canary seed, faba beans, soybeans, other legumes, potatoes, strawberries, carrots, parsnips, rutabagas, cooking onions, lettuce, other vegetables, tame millet, alfalfa, timothy, clovers, tame grasses, extended grazing forage, forage crops (excluding coarse hay) during the growing season, forage crops (including coarse hay) stored for the winter

Livestock: cattle, hogs, horses, sheep, donkeys, wild boar, goats, elk, fallow deer, bison, llamas, alpacas, ostriches, emus, and other ratites

Other animals: honey bees, leafcutter bees |

For damage to crops: bears, deer, ducks, elk, geese, moose, sandhill cranes, wood bison

For damage to livestock and poultry: bears, cougars, coyotes, foxes, wolves For damage to beehives, bee colonies and/or bee-related equipment: bears |

❌ |

| Ontario | ❌ | ✔️

|

✔️* only damage to bee related equipment is eligible

|

Livestock: alpaca, bison, cattle, deer, donkey, elk, emu, fisher, goat, horse, llama, lynx, marten, mink, mule, ostrich, rabbit, racoon, rhea, sheep, swine

Poultry: bobwhite (northern), chicken, duck, goose, grouse (ruffed, spruce, sharp-tailed), gray partridge (Hungarian), pheasant (ring-necked), ptarmigan (rock, willow), turkey (includes wild) Other Animals: honey bees |

For damage to livestock and poultry: bear, bobcat, cougar, coyote, crow, eagle, elk, fisher, fox, hawk, lynx, mink, raccoon, raven, vulture, weasel, wolf

For damage to bee-hives, bee colonies and/or bee-related equipment: bear, deer, raccoon, skunk |

❌ |

| Prince Edward Island | ❌ | ❌- can receive compensation through PEI Agricultural Insurance Corporation | ❌ | N/A | N/A | ❌ |

| Quebec | ✔️ | ❌ | ❌ | Crops: apples, autumn cereals, corn silage, cranberries, emerging crops, grain corn, Haskap berries, hay high-protein crops, maple syrup, market garden crops, potatoes, raspberries, semi-cultivated low-bush blueberries, strawberries, vegetables grown for processing; All crops eligible under the Crop Insurance Program (ASREC) are covered.

Other animals: honey bees |

For damage to crops: Canadian geese, ducks, snow geese, sandhill cranes | ❌ |

| Saskatchewan | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️* only damage to bee related equipment is eligible

|

Crops: all seeded commercial crops, including crops not currently insured by SCIC, stacked hay, silage and bales (in order to receive compensation, bales must be put into stacks. Producers will not be compensated for unstacked bales left in fields unless it is part of an alternative feeding system), market gardens, tree nurseries, sod farms, crops used for alternative feeding systems. Can also receive compensation for flood damage to seeded crop and tame forage due to beaver structures.

Livestock: cattle, sheep, goats, bison, horses, hogs (excluding wild boar), elk, fallow deer, llamas and donkeys, other less common species Poultry: Ostriches, emus, ducks, geese, chickens and turkey Other animals: honey bees, leafcutter bees |

For damage to crops: white-tailed deer, mule deer, antelope, elk, bears, moose, bison, wild boars, ducks, geese, blackbirds, sandhill cranes, gophers, beavers, other non-domestic species.

For damage to livestock and poultry: coyotes, |

✔️ - Producers can receive compensation for steps taken to prevent wildlife damage to feed supplies, with temporary fencing available to protect feed sources. Fencing for grain bag storage is not eligible. To qualify, a producer must first contact a customer service office and explain the wildlife problem. If deemed necessary, a predation specialist can also be hired to assess the situation and take steps to eliminate the predator problem. Funding can be acquired for:· Fencing around feed yards· Fencing to protect nurseries and market gardenProducers can also receive $100 to help offset the cost of purchasing a livestock guardian dog. |

| Yukon | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ - fences | No specified crops or livestock - eligible losses for compensation include damage to:

|

No wildlife species specified | ✔️ - Through the Canadian Agricultural Partnership’s Wildlife Damage Protection Program, agricultural producers in the Yukon can receive assistance to protect crops, market gardens, livestock, orchards and pasture lands through funding of pp to 50% of project costs with in-kind contributions, up to 60% if there are no in-kind contributions, to a maximum of $35,000 during the life of the program. |

Invasive species

Measures are also available to reduce invasive species that can sometimes trigger compensation claims. These are organisms that have intentionally or accidentally been introduced to a region where they are non-native through human activity, and negatively impact the native wildlife and ecosystems. In 2005, invasive species were ranked as the 6th greatest threat to Canadian SAR, affecting 22% of species (Venter et al., 2006). They have since risen in the ranks to become the 3rd greatest threat, now affecting just under half of all SAR (Woo-Durand et al., 2020). Invasive species not only directly threaten native species through increased competition for resources and habitat, they also can alter the actual biological conditions of an ecosystem, disrupting the way it functions and ultimately reducing its suitability for native species. For example, garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolate) is an edible herb brought over from Europe that has established itself in Ontario and parts of Quebec, invading forests and altering the soil composition so as to prevent beneficial fungi from bringing nutrients to the roots of other plants (Anderson, 2012). It has also spawned somewhat uncontrolled wildcrafting by humans that has added in many cases to ecosystem disruption. Zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) are well-established in the Great Lakes, and feed and breed rapidly, dominating available substrates and reducing turbidity, which allows sunlight to penetrate deeper, aquatic vegetation to grow larger, and toxic algae blooms to flourish, putting pressure on native species adapted to the regular conditions (DFO, 2021). In agricultural landscapes, invasive species similarly reduce the productivity of the soil and degrade water quality and quantity, and can also act as vectors for new crop diseases and pests (Canadian Council on Invasive Species, 2021). These factors reduce profit for farmers and increase management and mitigation costs, negatively impacting the functioning of our food systems.

Wild pigs, aka wild boars (Sus scrofa) are an incredibly destructive and rapidly expanding invasive species in Canada (being native to much of Eurasia and North Africa) that threaten both biodiversity and food systems through increased competition, predation, habitat destruction, and disease transmission (Koen, 2018). Introduced in the 80s and 90s (there were some 500 operations with 32000 pigs reported in the 2001 Census of Agriculture) as a new livestock species to bolster producer incomes, escapees and intentional releases (from both farms and wild game hunts) have resulted in feral populations that currently have a range of almost 800,000 km2 across 6 provinces, with the largest concentration across Saskatchewan (Aschim & Brook, 2019; see also maps in Pruden, 2022), although there are no precise estimates of their populations. Their growth has been exponential due to their life history characteristics; wild pigs have “extremely high fecundity, early sexual maturity, plastic diet[s], long lifespans, and [a] highly adaptive nature” (Aschim & Brook, 2019, pg. 1). While these pigs have already expanded a considerable range, many more areas in Canada, especially those with energy-rich crops, forest cover, and low predator densities are extremely susceptible to colonization by wild pigs, populations of which are projected to continue to grow exponentially over this next decade if there are no interventions (Aschim & Brook, 2019). US estimates suggest 70% of the population has to be removed annually just to keep it from expanding (Pruden, 2022).

Biodiversity conservation in agriculture

Perhaps inspired by Canada's Biodiversity Conservation Strategy, the first Agricultural Policy Framework (APF) identified biodiversity conservation as a priority area although targets and performance measures were not yet well developed and data was limited because of decisions made regarding the confidentiality of Environmental Farm Planning. Two environment pillar programs were implemented to improve on-farm biodiversity - Environmental Farm Planning and the Greencover Program - but their effectiveness was limited, and significant criticisms were leveled at both programs. Subsequent APFs (Growing Forward I and II; Canadian Agricultural Partnerships) have not substantially addressed these limitations while altering the suite of environmental programs. However, some provinces have retained funding under the CAP for biodiversity conservation work, including Saskatchewan's Farm Stewardship program which funds on a cost-share basis BMPs related to grassland protection

Other initiatives have emerged, including conservation agreements with agricultural land owners in Manitoba to protect bird habitat operated by the Manitoba Habitat Heritage Corporation (MHHC). They also run a program with beef producers protecting grasslands, and funded by Environment and Climate Change Canada. Projects are funded on a cost-share basis, up to $50000 / farm, for implementation of a number of best management practices. Some of the programs are offered in conjunction with NGOs.

In theory, this approach is governed by the Land Sparing-Sharing (LSS) concept, balancing sustainable, productive land-use and biodiversity conservation, through either “separating intensive agricultural land from biodiversity-rich wildlife spaces” (land sparing) or integrating wildlife and ecosystem-friendly practises into productive areas to promote coexistence (land sharing) (Green et al., 2005). Most of the Canadian initiatives on farms are about practising intensive agriculture on the so-called "productive" spaces and then leaving some biodiversity around the edges.

Protected areas (PAs)

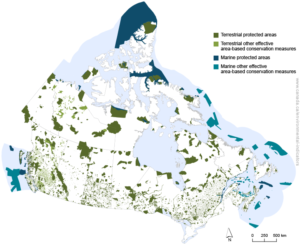

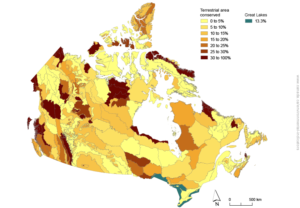

Canada generally favours the separation of land and aquatic zones from productive spaces and has numerous terrestrial or marine protected spaces. Most of them are concentrated in remote regions, separated from agriculture and the main fisheries (Venter et al., 2018, pg. 127; Mitchell et al., 2021). Much of the main agricultural areas have no protected areas, and what does exist generally falls into the category of other effective conservation measures (Figure 1, 2).

Figure 1: Conserved areas in Canada. “The map of Canada shows the distribution and size of terrestrial (land and freshwater) and marine protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures in 2020”. Reproduced from ECCC Canada’s Conserved Areas (2020).

Figure 2: Proportion of area conserved, by ecoregion, Canada, 2020. “Area conserved includes area protected as well as area conserved with other measures. Data are current as of December 31, 2020.” Reproduced from ECCC Canada’s Conserved Areas (2020).

94% of protected terrestrial areas and 64% of the protected marine territory are conserved through PAs and MPAs respectively (Figure 1). The remaining percentages are protected through what is termed “other effective area-based conservation measures” or OECMs, recognized formally in 2017 – 2018. OECMs are “geographic spaces governed and managed in ways that achieve sustained results for the conservation of nature even if their primary purpose is not nature conservation”, and may include places like historic sites, military training areas, and hunting reserves (Dudley et al., 2018; Parks Canada, 2021a).

Terrestrial (including freshwater) protected spaces are governed by a complex array of instruments. On the legislative side, federally they include the Canada National Parks Act, with some spaces also governed by the Canada Wildlife Act, Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, the Species at Risk Act, and the Migratory Birds Convention Act. There are also numerous policies related to specific habitats and regions. The provinces also have an equally complex set of legislation and policy. Aboriginal communities also govern some protected spaces (see Goal 1, Self- and community provisioning) and a small percentage are governed by private landowners and NGOs, often through land trusts (see Goal 3, Reducing Corporate Concentration, Substitution, Land).

Marine spaces are protected in a variety of ways, with Marine Protected Areas under the Oceans Act, and others under the Canada Wildlife Act, and the Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act. See Goal 5, Sustainable Fisheries Management.